Executive Summary

Hinduphobic tropes — such as the portrayal of Hindus as fundamentally heretical evil, dirty, tyrannical, genocidal, irredeemable or disloyal (Viswanathan) — are prominent across the ideological spectrum and are being deployed by fringe web communities and state actors alike. Despite violent and genocidal (Rummel, 1994) implications of Hinduphobia, it has largely been understudied, dismissed, or even denied in the public sphere. This report applies large scale quantitative methods to examine the spread of anti-Hindu disinformation within a wide variety of social media platforms and showcases an explosion of anti-Hindu tropes. Though confined largely to street-level groups and enthusiasts in the recent past, Hinduphobia is now exploding across entire Web communities across millions of comments, interactions and impressions in both mainstream and extremist platforms.

Introduction

Platforms, civil society organizations, and media are largely unfamiliar with Hinduphobia (Viswanathan). This paper seeks to rectify this state of affairs and deploys a data-driven approach, consisting of large-scale quantitative and machine learning analysis of a wide variety of social media data, to understand anti-Hindu disinformation and propaganda, which drives Hinduphobic discourse.

This approach is warranted because, with the advent of social media, early qualitative analysis suggests that anti-Hindu disinformation and propaganda in the form of memes and hashtags is currently growing prolifically on online platforms (Balaji and Sachi, 2017). Such activity often heralds ethnic violence (Relia et al., 2019). These developments thus underscore that both qualitative and quantitative analyses of anti-Hindu disinformation are critically important for purposes of both scholarship and for protecting vulnerable communities.

Our analysis demonstrates that there is an alarming, recent rise in the use of key terms — particularly, anti-Hindu slurs and slogans — that both connote and disseminate Hinduphobia on popular social media platforms. Accompanying this increase is the proliferation of anti-Hindu genocidal memes in Islamist, white nationalist, and other extremist sub-networks online. While such developments are often mistakenly categorized as anti-Indian xenophobia, we show that the specific content of these memes, hashtags, and derogatory messages very clearly targets decidedly Hindu symbols, practices, and livelihoods. In so doing, these online communities are adapting a pre-existing, albeit understudied, playbook of Hinduphobic tropes to a new sphere of communication.

We also show that the percolation of Hinduphobia into general online discourse is used by a variety of both established and emergent actors for political purposes. In particular, we show that state actors within Iran often weaponize this discourse to ignite conflict between India and Pakistan. The weaponization of Hinduphobia for facially political aims in the real world poses a tangible threat to ratchet anti-Hindu violence.

Organized non-state actors such as ISIS, are also expanding Hinduphobic attacks and propaganda. On June 19, 2022, ISIS-K terrorists attacked a Sikh Gurudwara in Afghanistan in “revenge” for allegedly blasphemous comments made by an Indian politician. Official ISIS-K propaganda outlets claimed that the terrorists “penetrated a temple for Hindu and Sikh polytheists in Kabul, after killing its guard, and opened fire on the pagans inside with [their] machine gun and hand grenades” (France-Presse, 2022).

As ethnic tensions and violence begin to mount in the subcontinent (MEMRI, 2022), knowledge of Hinduphobic tropes is now a critical asset for the media and platforms because anti-Hindu tropes are rapidly cycling from the cyber social sphere to the kinetic sphere in an atmosphere of populist violence. We therefore emphasize that this study is both timely and foundational: it exposes a growing spate of online hatred that has mushroomed in the dark; a hatred that increasingly portends real-world consequences.

Sources and Methods

In order to understand anti-Hindu disinformation throughout history, along with its manifestations via modern-day memes, we utilized OSINT (open source intelligence) collection, machine learning, natural language processing, and time series analysis as a part of a broad toolkit of quantitative methods.

Data Aggregation

Social Media Data

For our contemporary analysis, we collected anti-Hindu hashtags and comments from popular social networking and messaging platforms — Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, 4Chan, Gab, and Telegram. Several open source Python scraping libraries and APIs were used to extract data from these social media platforms. For Twitter, we used snscrape to extract tweets with hashtags and keywords of interest. In addition, we examined state-sponsored trolls from Iran using the Twitter Information Operations Dataset. For more fringe communities such as 4Chan, Gab, and Telegram, we used the Social Media Analysis Toolkit (SMAT) application’s API, querying for keywords to receive all comments from 2019 - 2022.

Data Analysis

Time Series Analysis

Our data ranges from January 2019 to January 2022 for comments in our community sample, and until March 2022 for more fringe web communities. From this data, we examined the usage of these terms over time on a time series graph.

Hashtag Frequency and Ranking

For the tweets examined, we ranked the top hashtags associated with the ethnic slurs and anti-Hindu terms identified from the OSINT collection.

Word2Vec Models and Topic Networks

From the scraped data, we used Spacy to tokenize the sentences to remove stop words (e.g., prepositions, articles, pronouns: words which do not add value to our analysis) and also lemmatize — group together — words based on their roots. This was then trained on Word2Vec (Zannettou et al., 2018): artificial neural networks which identify contextual word associations by scoring their vector destinations in linguistic space. Contextual proximity is scored by the calculated cosine similarity value in the model between words. Using the trained Word2vec model, we developed topic networks which use clustering algorithms to group like terms. The size of a term indicates its volume.

Vector Subtraction

In order to uncover underlying anti-Hindu themes, we leveraged vector theme subtraction (Vylomova et al., 2016). Typically, extremists use memes, codewords, and dog whistles to convey anti-Hindu messaging. To understand whether or not the messages were tagged to Hindus, we used theme subtraction — a methodology in computational linguistics to remove related semantic components and return the result. A simple example is “king - man = ruler” (arXiv, 2015).

In topic networks, we conducted vector subtractions by removing the “Hindu” component and examining the impact on the content of the topic network. In particular, when vector subtracting “Hindu” from these networks, we would expect the remainder to have weak hateful information content if the underlying (coded) animosity in the language was directed at Hindus.

Anti-Hindu Disinformation is Masked Through the use of Ethnic Pejoratives, Slurs, and Coded Language

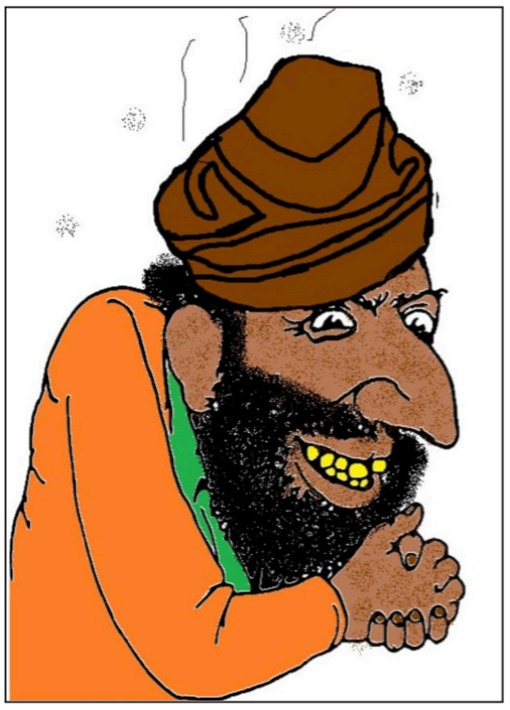

Figure 1 shows the Hindu version of the Happy Merchant meme; typically, the happy merchant meme is an emblem of antisemitism, but has also been repurposed in creating other anti-Asian memes. The Happy Merchant became popularized by white supremacists and far right communities to disseminate Antisemitic speech online.

First seen on 4Chan, the term “pajeet” is an ethnic slur, coined as a derisive imitation of Indian names. Typically, pajeet is used to describe Indians on the Internet — and, by default — Hindus. John Earnest, the white supremacist shooter of the Chabad Synagogue in San Diego, 2019, had referenced “pajeets” (BCSH, 2019) in this manifesto. This slur has also been used by white supremacists in white nationalist podcasts in reference to violent, murderous fantasies about Indians (Hayden, 2020).

Our qualitative analysis suggests that pajeet is used in reference to Hindus and Indians interchangeably, with the majority of derogatory characterizations targeted towards Hindus. In particular, distinctly Hindu symbols (swastika, tilaks, etc.) are used persistently in memes referencing pajeet, while the analogue is not true for imagery specific to Islam, Christianity, or other religions within India.

Figure 1: The Hindu version of the Happy Merchant Meme titled “Poo in the Loo”

Figures 2, 3, 4, 5: Anti-Hindu Genocidal Memes

Islamist extremist and white supremacist communities regularly disseminate genocidal and violent propaganda and memes against Hindus. Through our open-source intelligence collection for comments and images related to pajeet, we found open calls for genocide disguised using coded language. We found that the messaging is not limited to Islamic extremists. In all figures here, extremists leverage “Pepe the Frog” — an emblem of white supremacy and the alt right (Glitsos and Hall, 2019) — within violent memes to enliven their genocidal fantasies.

For instance, in Figure 2, self-identified Pakistani Islamist accounts mock the 26/11 terrorist attack in Mumbai, in which 175 people were killed by Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists (Bhandarwar et al., 2012). There is a clear demarcation between the terrorists (depicted as variants of “Pepe the Frog”) and the survivors/victims, whose Hindu identity is particularly emphasized with brownface, saffron clothing, and tilaks. Hindu victims are shown crying, frustrated, and powerless, while Islamist terrorists are depicted as impervious and smug, reveling in the violence.

Islamists borrow genocidal motifs from well beyond India, including Nazi Germany and the contemporary United States. For example, in Figure 3, Islamists co-opt the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin to suggest the same dehumanizing treatment should be meted out to Hindus. Further memes illustrate Pepe the Frog (as an Islamist) fashioned as an SS officer — clear from the Nazi flag and emblem on his arm — gassing a Hindu male, depicted with saffron and a swastika (Figure 4); and the same character enacting an ISIS-style beheading of Hindus foregrounded against a terror bombing (Figure 5).

A Rise in Anti-Hindu Slurs on Fringe Web Communities

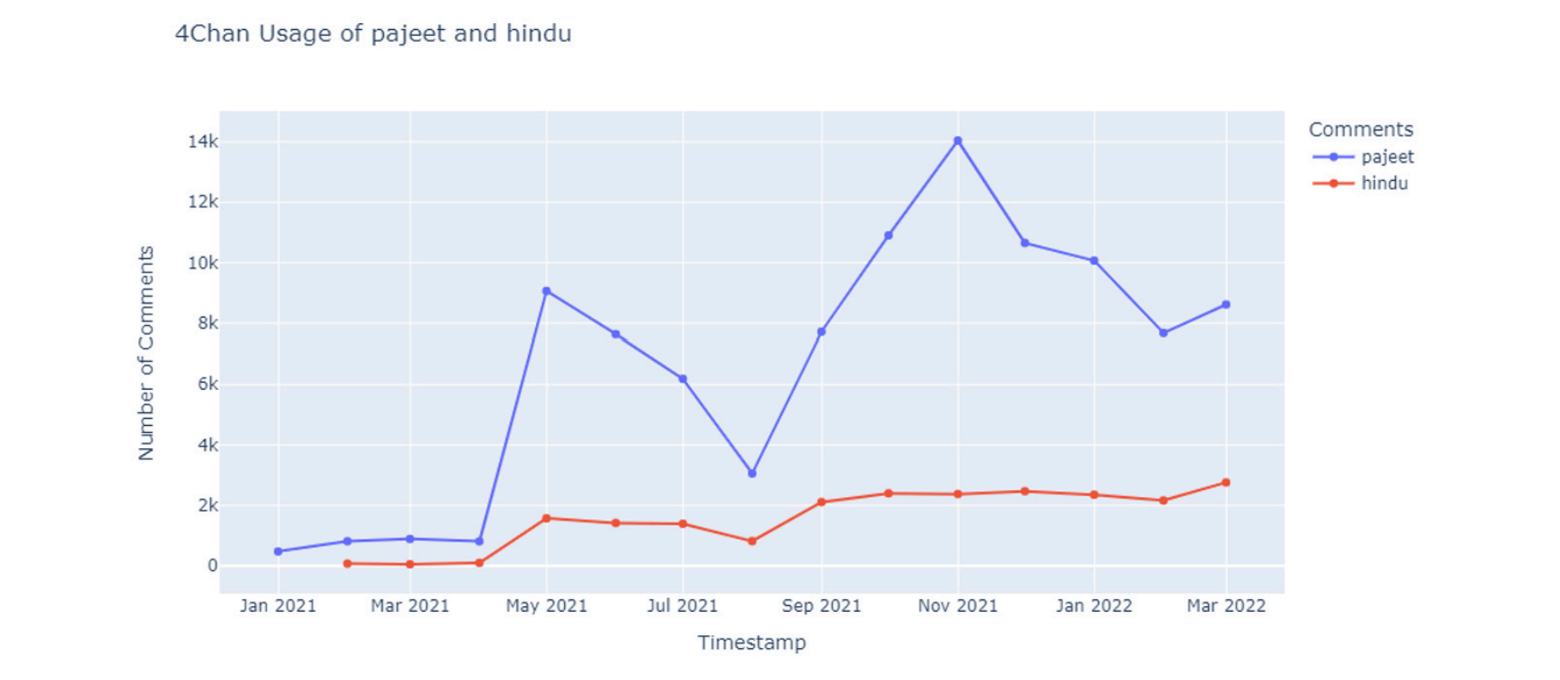

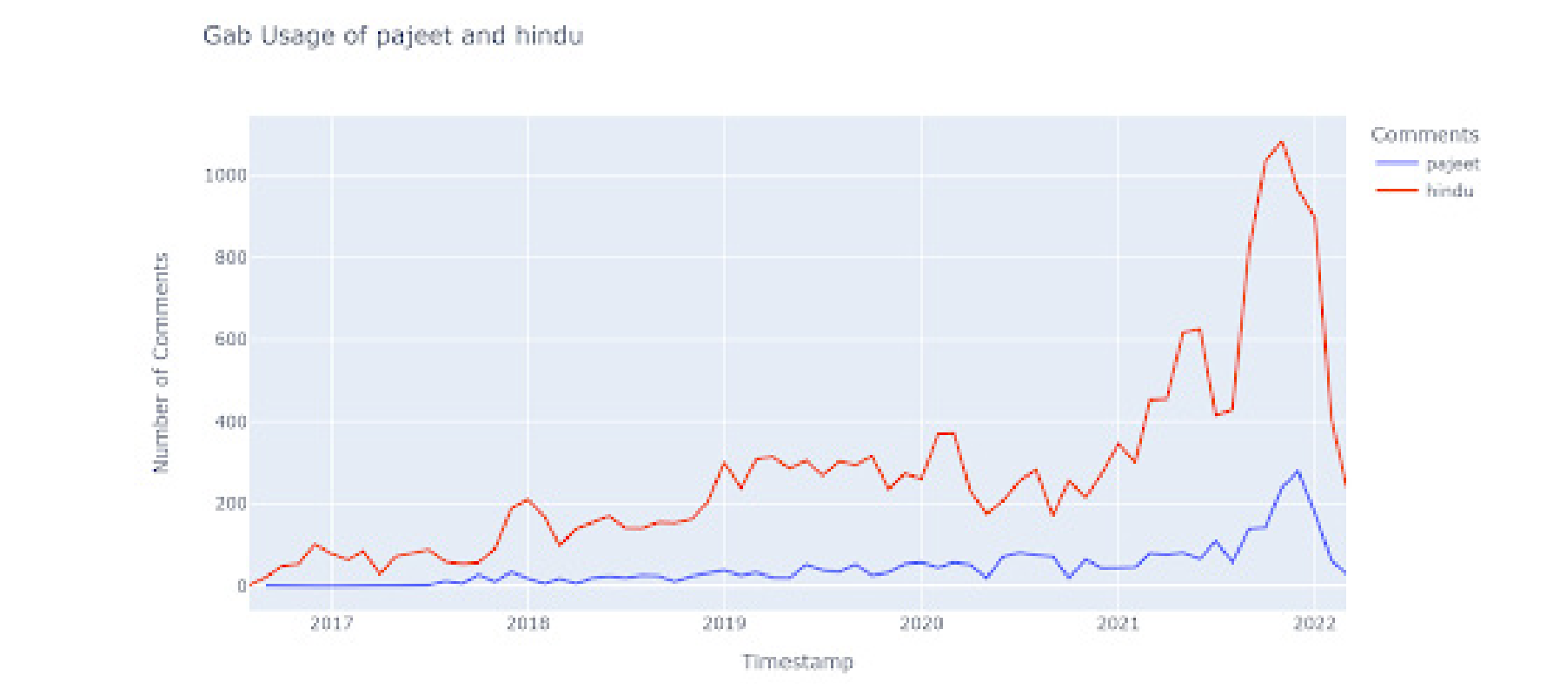

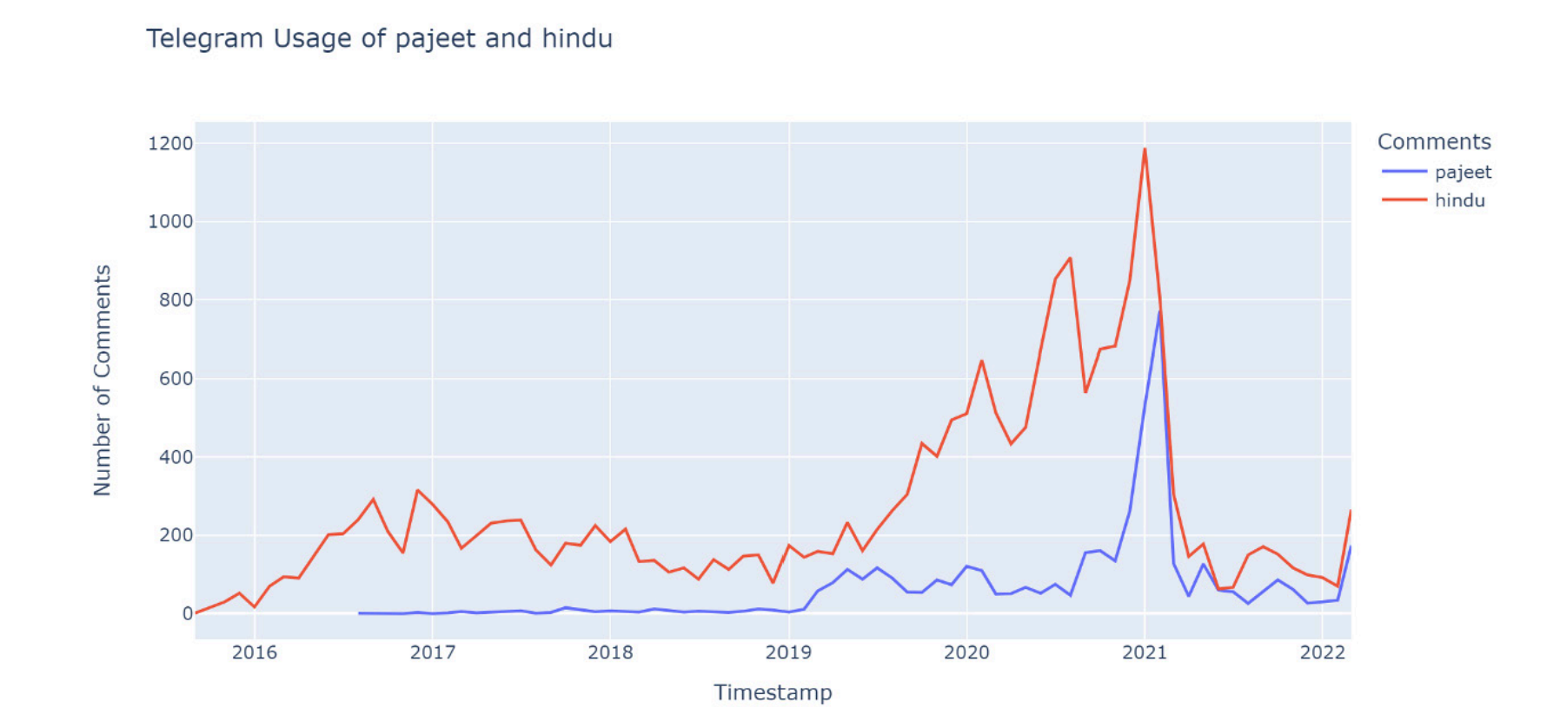

Our quantitative analysis suggests that usage of pajeet in such contexts is growing prolifically on fringe platforms. Using data from the SMAT application, we conducted a time series analysis of the term “pajeet” and “Hindu” on 4Chan, Gab, and Telegram.

Figure 6: Time Series Analysis of “pajeet” on 4cChan, Gab and Telegram

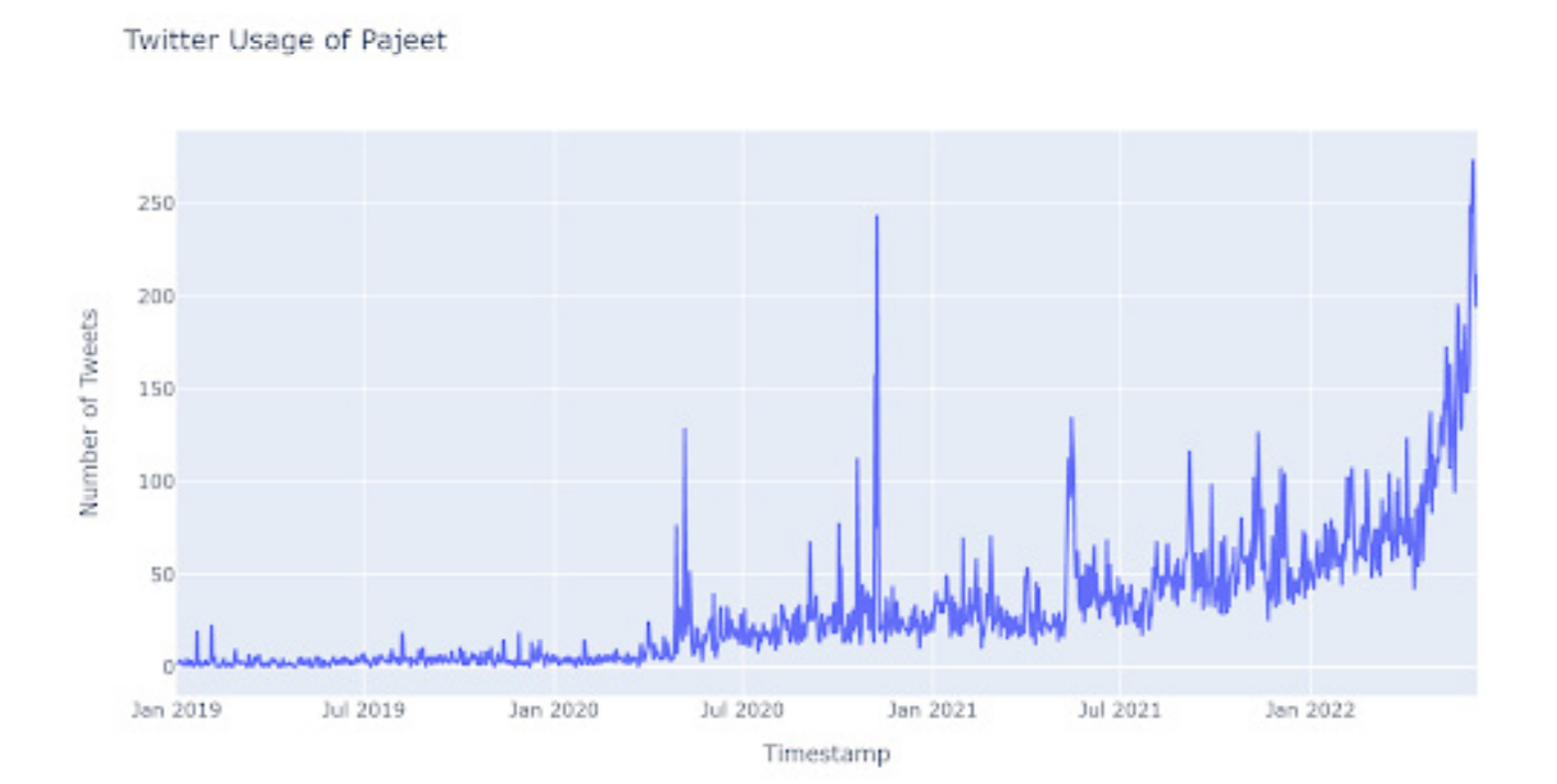

Figure 7: Twitter usage of “pajeet,” from January 2019 - June 2022

The use of “pajeet” is also growing on mainstream social media platforms, such as Twitter. Initially, this term hardly had any usage back in 2019 but picked up prominence in 2020 and is now being used more than 250 times a day.

We also found associated hashtags with Pajeet on Twitter. Spikes in the data correspond to key events. For instance, after the appointment of Parag Agarwal as Twitter CEO in late November 2021, there were surges in the usage of “pajeet” (Goforth, 2021). In addition the anti-Hindu bias has grown popular enough to reach the point of having its own cryptocurrency. Pajeet coin – a meme-based cryptocurrency, banks on the appeal of anti-Hindu tropes.

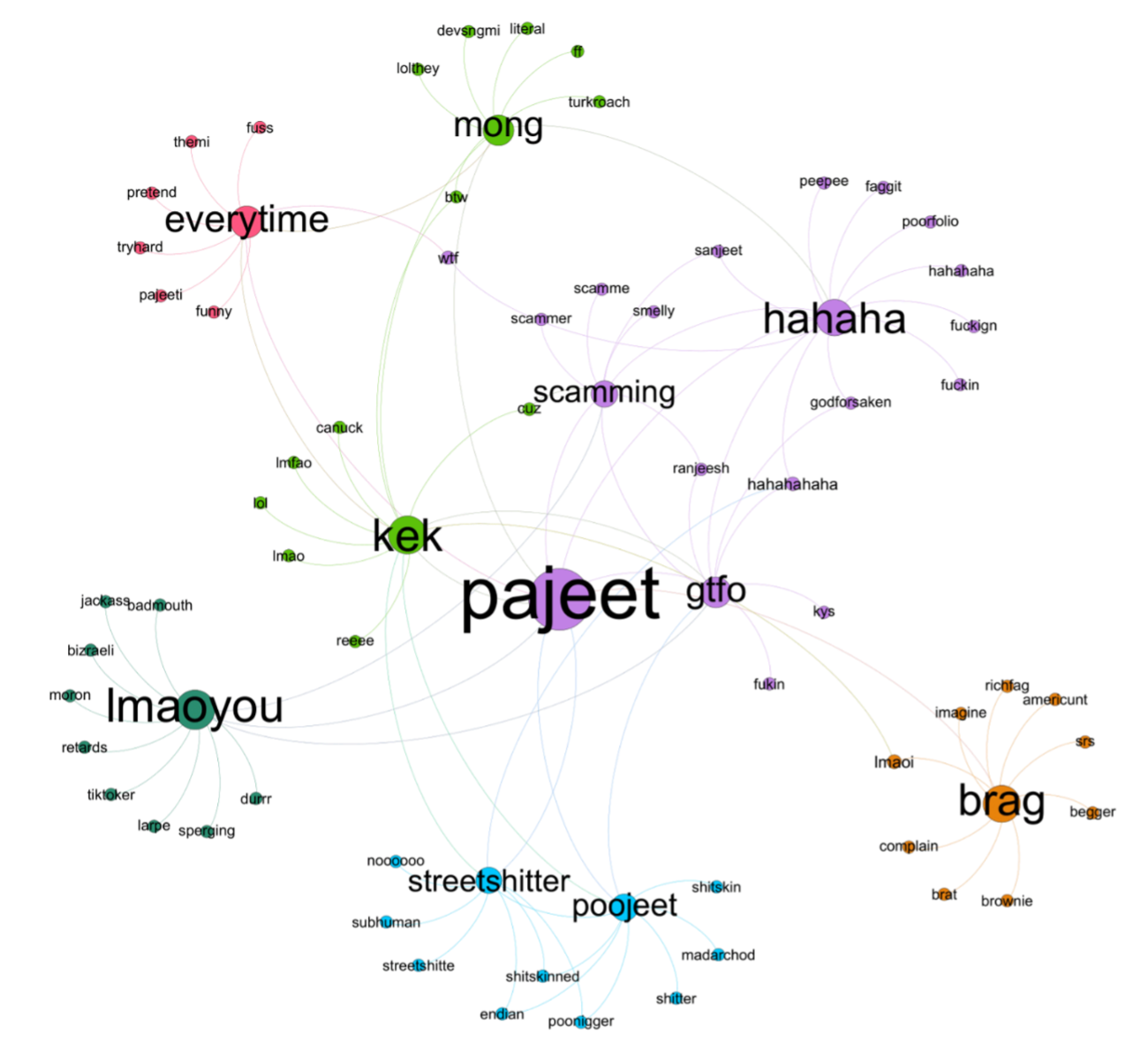

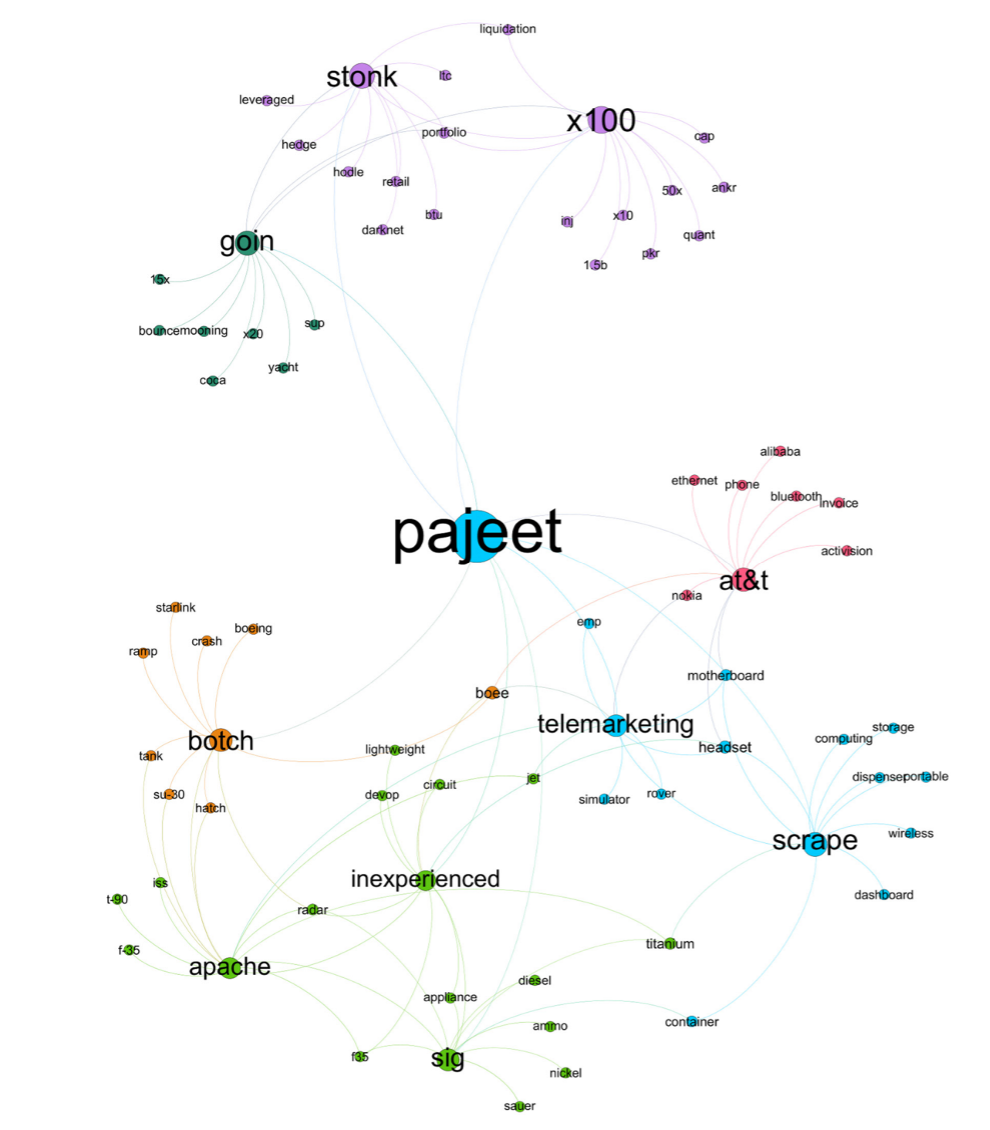

To further understand the tropes associated with “pajeet,” “hindu” and “india” on these platforms, we developed a two hop topic network on these terms from 4Chan.

Figure 8: Two hop topic network of “Pajeet” on 4Chan

Several clusters from the topic network indicate several themes of the same nature — the idea that pajeets (Hindus) are dirty (streetshitter, poojeet), dishonest (scamming), and unintelligent (mong — a slang term on 4Chan for individuals who do idiotic or stupid actions without realization). We see an entire cluster in blue, dedicated to dehumanizing depictions such as “shitskinned,” “subhuman,” and “poon***r.”

These derogatory characterizations are often accompanied by visual memes that depict Hindus as dirty, Islamophobic and barbaric.

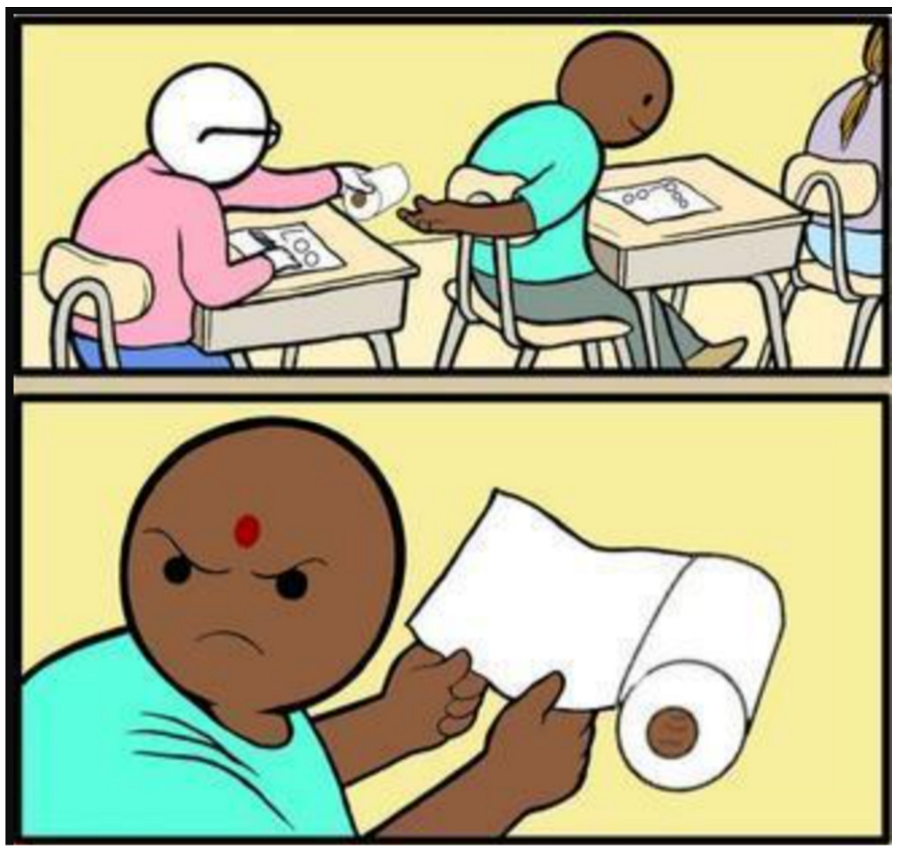

The note passing meme depicts a white student trolling a Hindu student (as shown with a bindi) by passing them toilet paper in the middle of class, causing the student to become outraged.

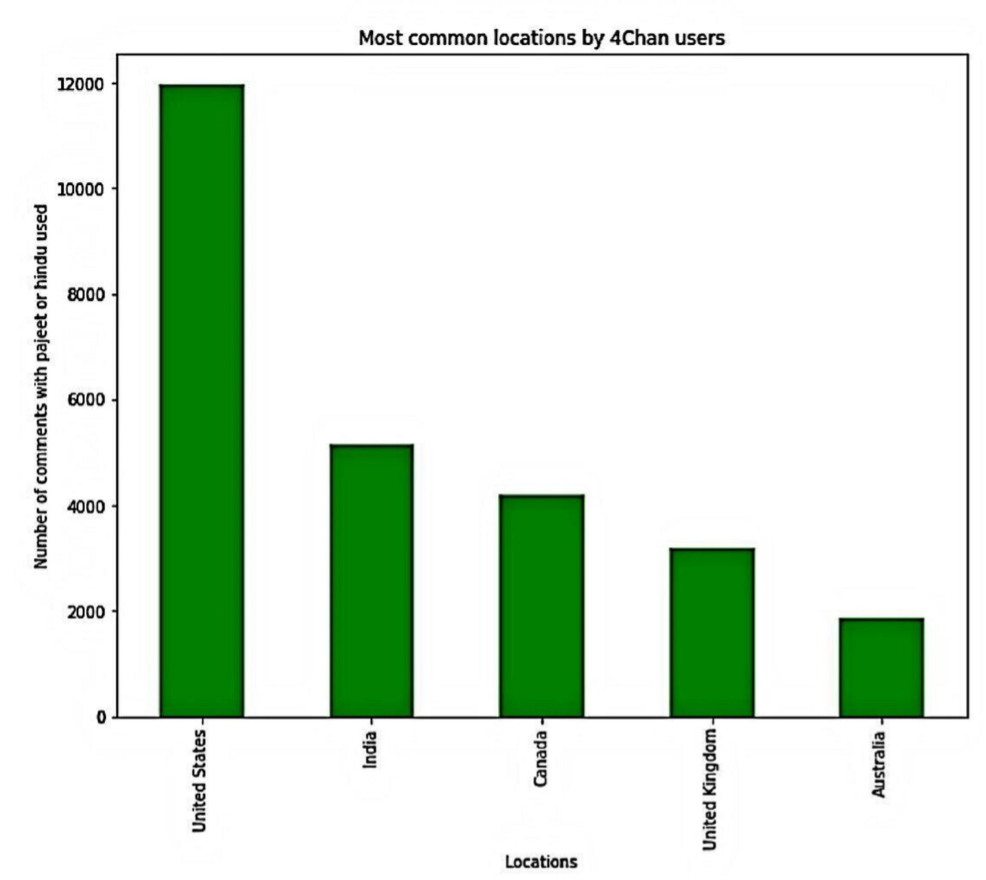

We also found that users commenting about “Pajeets,” “Hindus” and “India” on 4Chan self-reported their locations in the U.S., India, Canada, UK, and Australia, with the overwhelming majority being located in the U.S.

Figure 9: Note passing meme found on 4Chan titled “Indians will replace you”

Figure 10: Most common self-reported locations by 4Chan users

To quantitatively understand whether the tropes were tied to Hindus, we performed a vector subtraction of “Hindu” from the topic network of “pajeet,” removing the “Hindu” themed-components and then examined the words remaining in the topic network.

What Happens When You Take Away Hindu From Pajeet?

When removing all words associated with “Hindu,” the themes of dehumanization, dirtiness, and immorality immediately disappear. What remains is fluff terms with regards to economics and finance. This goes to show that the characterizations are not about “pajeets” per se or other ethnicities — but tied to the portrayal of Hindus.

Figure 11: Pajeet on 4chan minus Hindu (vector sub)

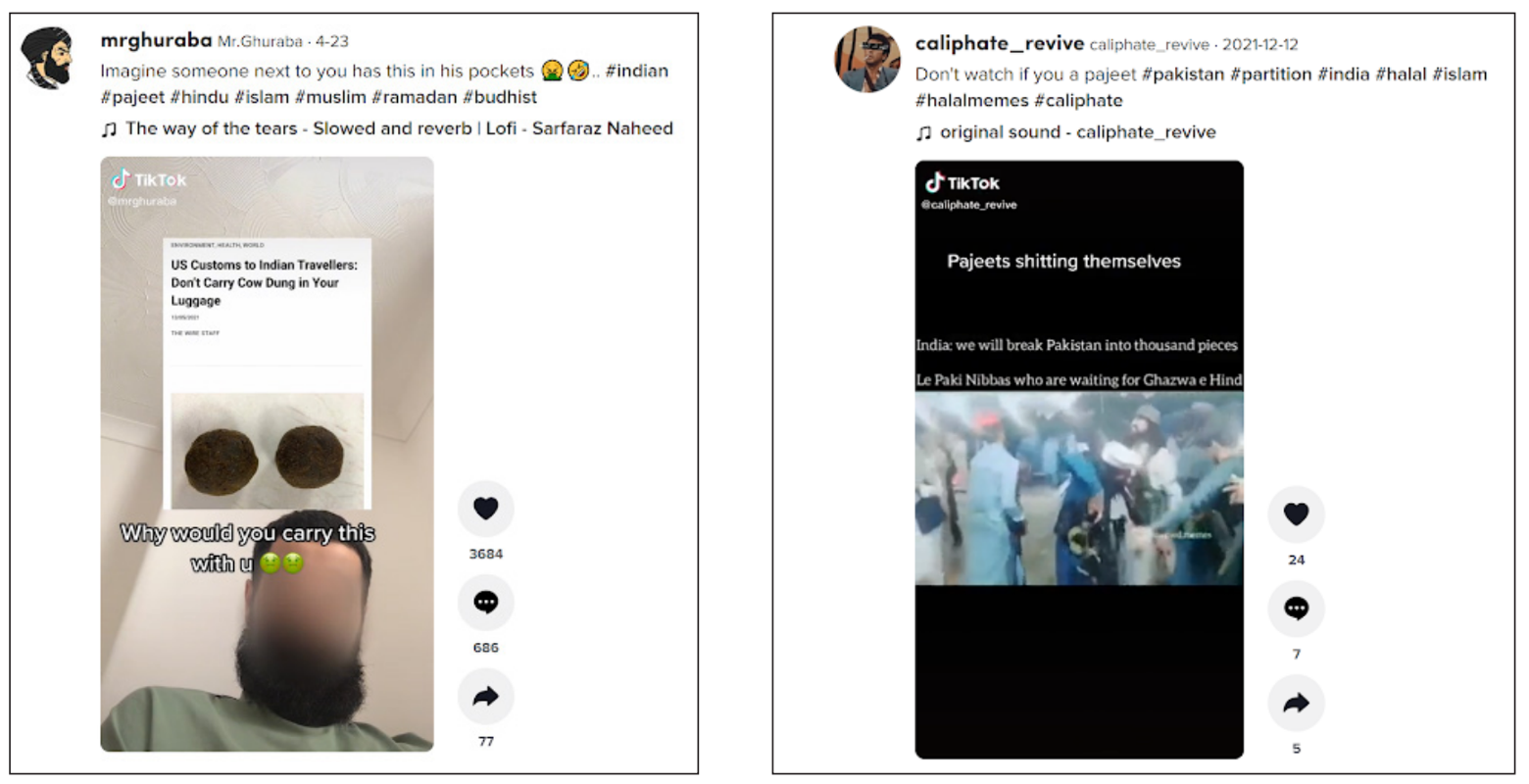

Live Streaming and Memeing Hinduphobia: Contemporary usage of Pajeet on Tiktok, Twitter, and Reddit

On Tiktok, videos containing “pajeet” in the captions have amassed close to 2.9 Million views. Such videos contain the same tropes as found in 4Chan (i.e. the idea of Hindus being dirty streetshitters), as well as open calls to violence and colonization of Hindus.

Figure 12: Tiktoks with “pajeet” in the captions

Accounts titled “Caliphate Revive” call for “Ghazwa-e-Hind,” a violent fantasy by Islamists to colonize India (Singam, 2020). Similar calls to violence are echoed on Twitter.

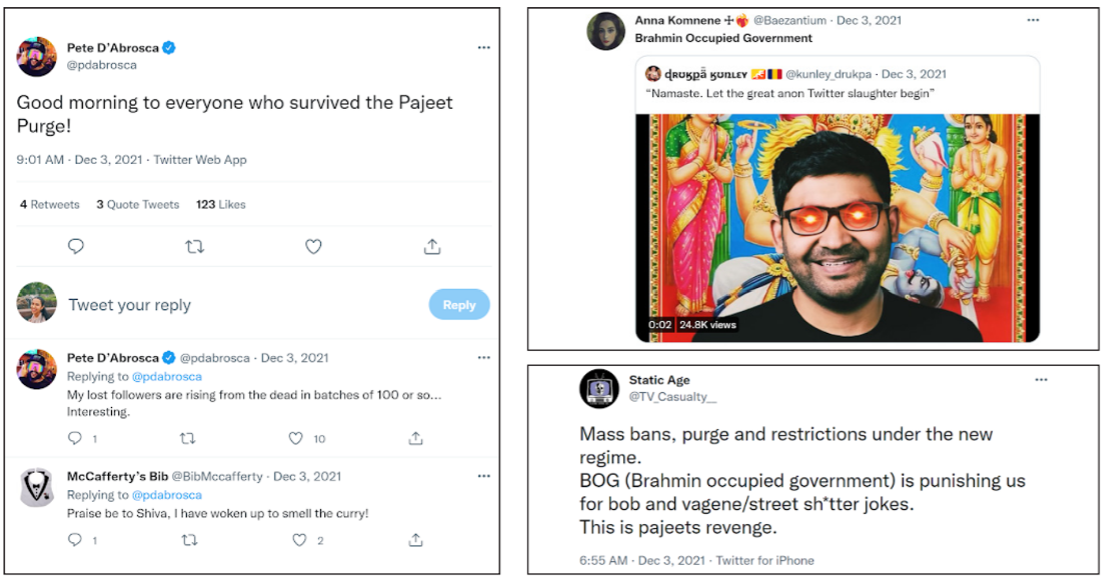

Figure 13: Mockery of Hindus and Calls for Violence on Twitter

Similar anti-Hindu themes are echoed by white supremacist communities. The idea that Hindus are “pajeets” who are dirty, backwards and perverted. After the appointment of Parag Agarwal as Twitter CEO, white supremacist accounts were quick to comment on the “pajeet purge” accusing Agarwal of deliberately mass censoring accounts. Furthermore, white supremacist communities borrow antisemitic tropes - such as the idea of a “Zionist Occupied Government,” a conspiracy theory used in several antisemitic manifestos which denote conspiracy theories about Jewish control over government and media - and use it against Hindus through the dog whistles of “Brahmin Occupied Government” relaying themes about Hindu dominance and control in places of power.

Figure 14: Twitter Comments on “pajeet purge”

Iranian State Sponsored Trolls

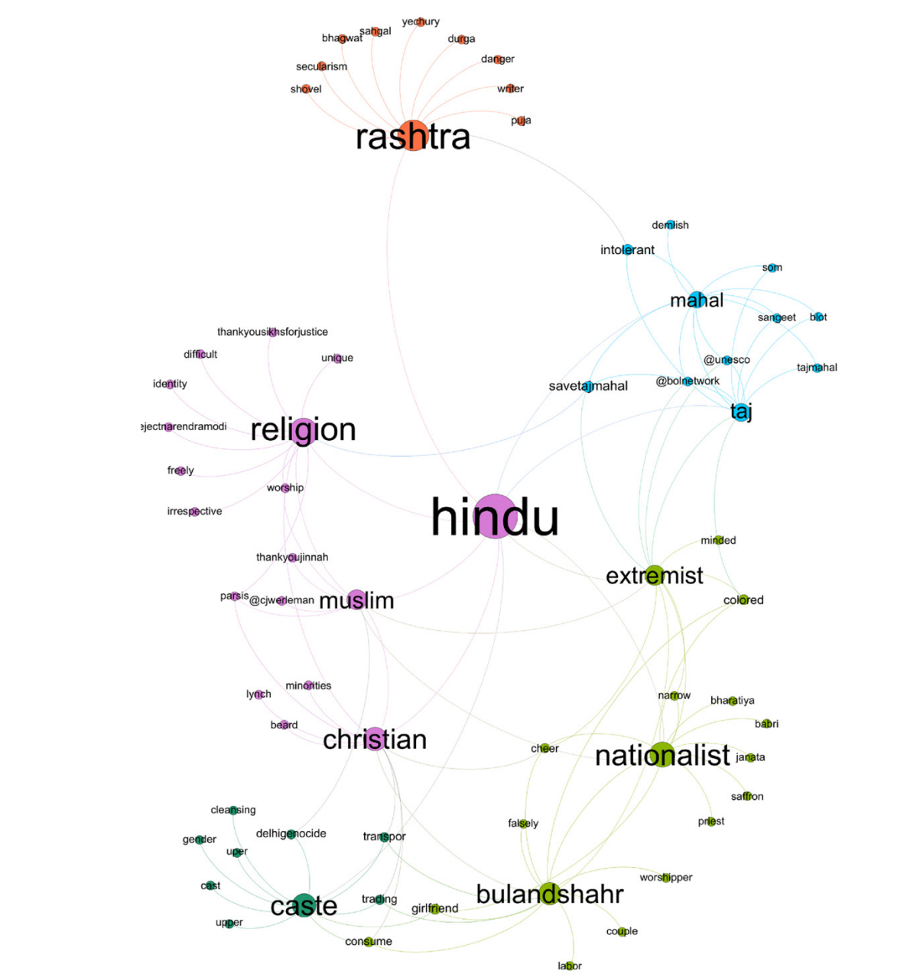

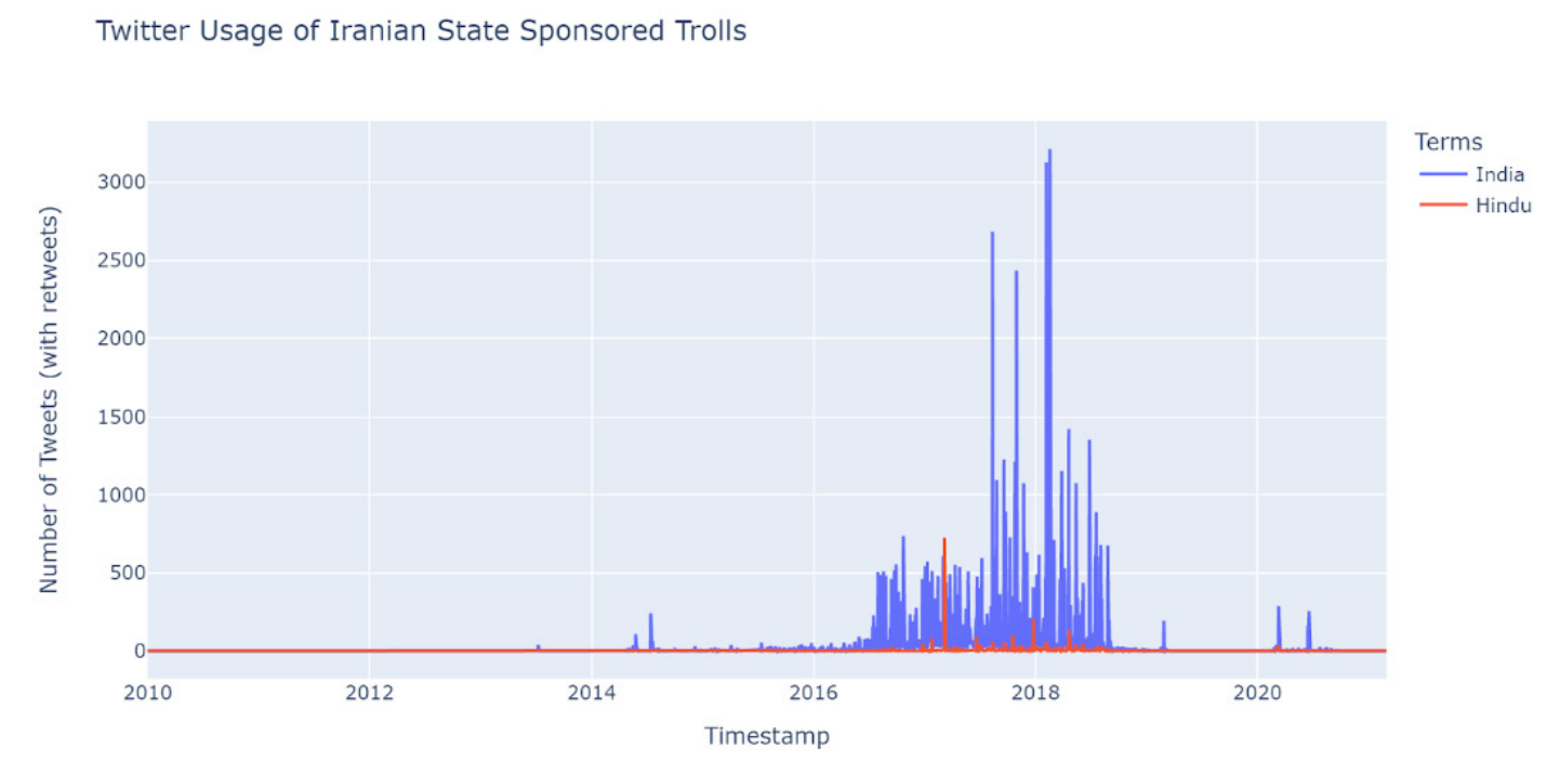

In addition to extremist groups and fringe web communities, state actors also deploy anti-Hindu tropes as part of information operations for geopolitical influence. Twitter releases an information operations dataset, which provides information on state sponsored Twitter accounts. Using this dataset, we examined 1,766,301 tweets from state sponsored Iranian trolls from 2010 to 2021. Analyzing this data, we developed a topic network for “Hindu” as well as a time series analysis for “Hindu” and “India.”

Figure 15: Two Hop Topic Network of Hindu from Iranian trolls from 2010 - 2021

Our topic network showed that Iranian trolls disseminated anti-Hindu stereotypes, such as associating Hindus with extremists who perpetrated violence against minorities (Muslims, Christians), and inflaming caste divisions between communities.

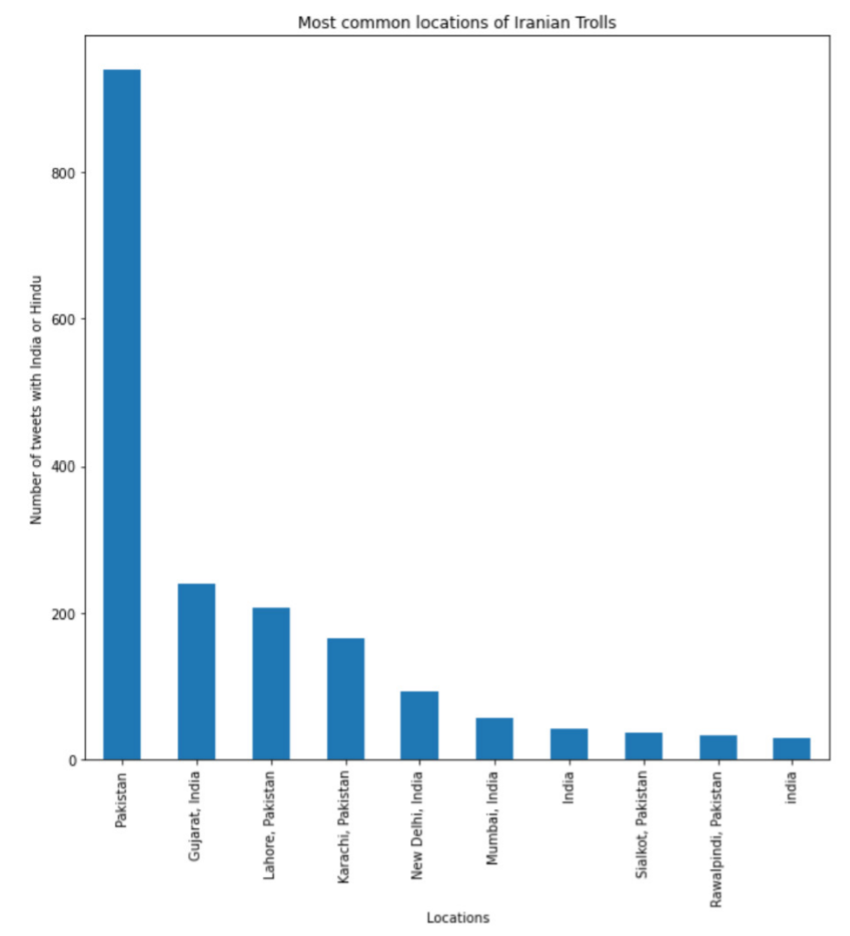

Furthermore, our analysis suggests the use of covert influence in the Anti-Hindu disinformation used by Iranian state sponsored trolls, presumably as a tool for provoking political unrest. Our location analysis of Iranian trolls found that the self-reported location of such users tweeting about India or Hindus was highly clustered in Pakistan, with some anti-Hindu account locations in India as well. That they are Iranian state actors therefore indicates that these users were strategically falsifying their location. This suggests efforts by the Iranian regime to inflame ethnic tensions in both domestic and inter-state conflicts between Muslims and Hindus and showcases the use of Hinduphobic disinformation for geopolitical strategy.

Figure 16: Locations of Iranian State Sponsored Trolls

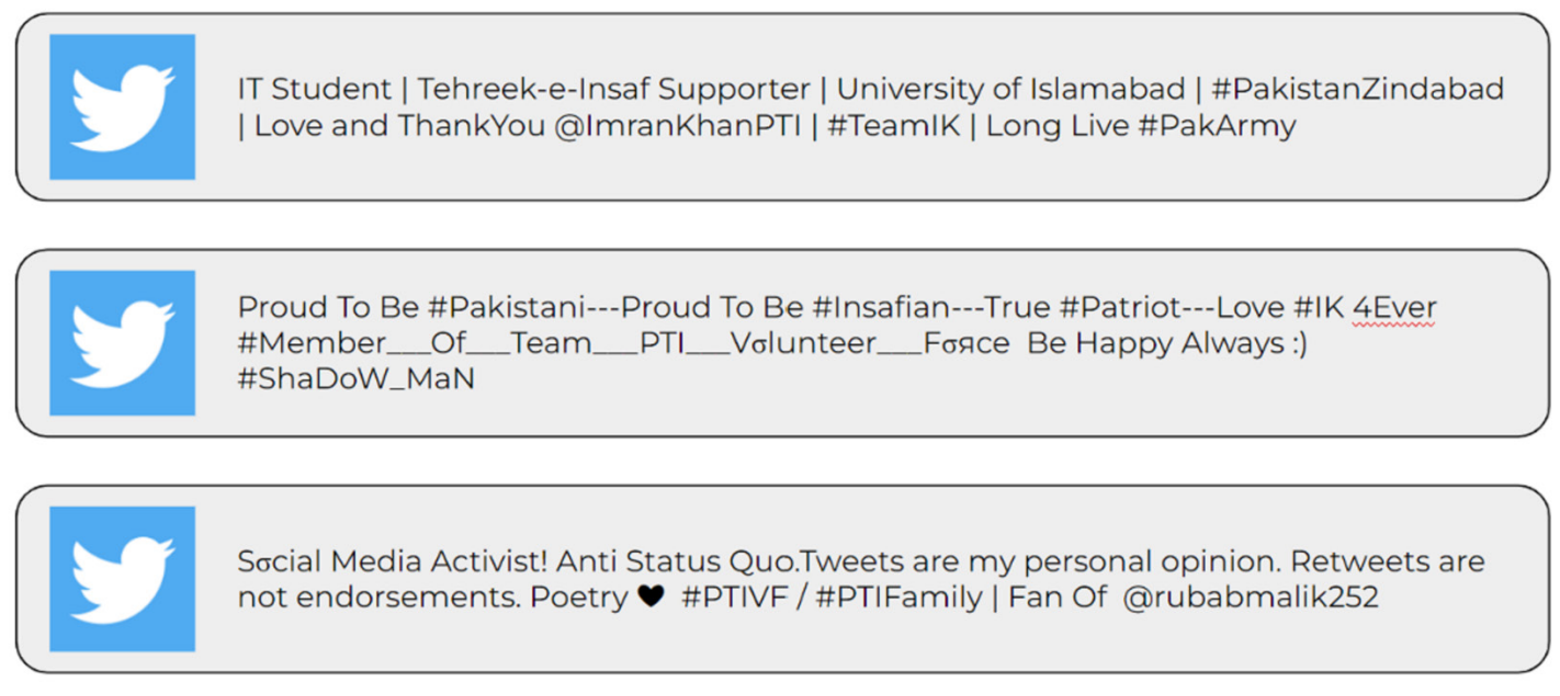

In a predominant set of cases, these trolls specifically pretend to be Pakistani supporters of Imran Khan and the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) political party. Below is a sample of the top user descriptions, each of which has the location set to Pakistan:

Figure 17: Time Series Analysis of terms relating to Hindus and India

Iranian trolls tweet about India and Hindus during times of geopolitical conflict. For example, during the March 2017 Bhopal–Ujjain Passenger train bombing by ISIS, Iranian trolls, pretending to be Pakistani, attempted an influence operation and disinformation campaign to suggest that the attack was done by “Hindu Extremists,” and attempted to get it trending. In August 2017, Iranian trolls surged the hashtag #KashmirDeniesIndia during the time of unrest in the region following the death of Hizbul Mujahideen (U.S. Department of State) terrorist Burhan Wani. A subsequent spike in early 2018 predates the visit of Iranian President, Dr. Hassan Rouhani to India (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2018). During his visit, Iranian trolls tweeted 1,053 times about human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir.

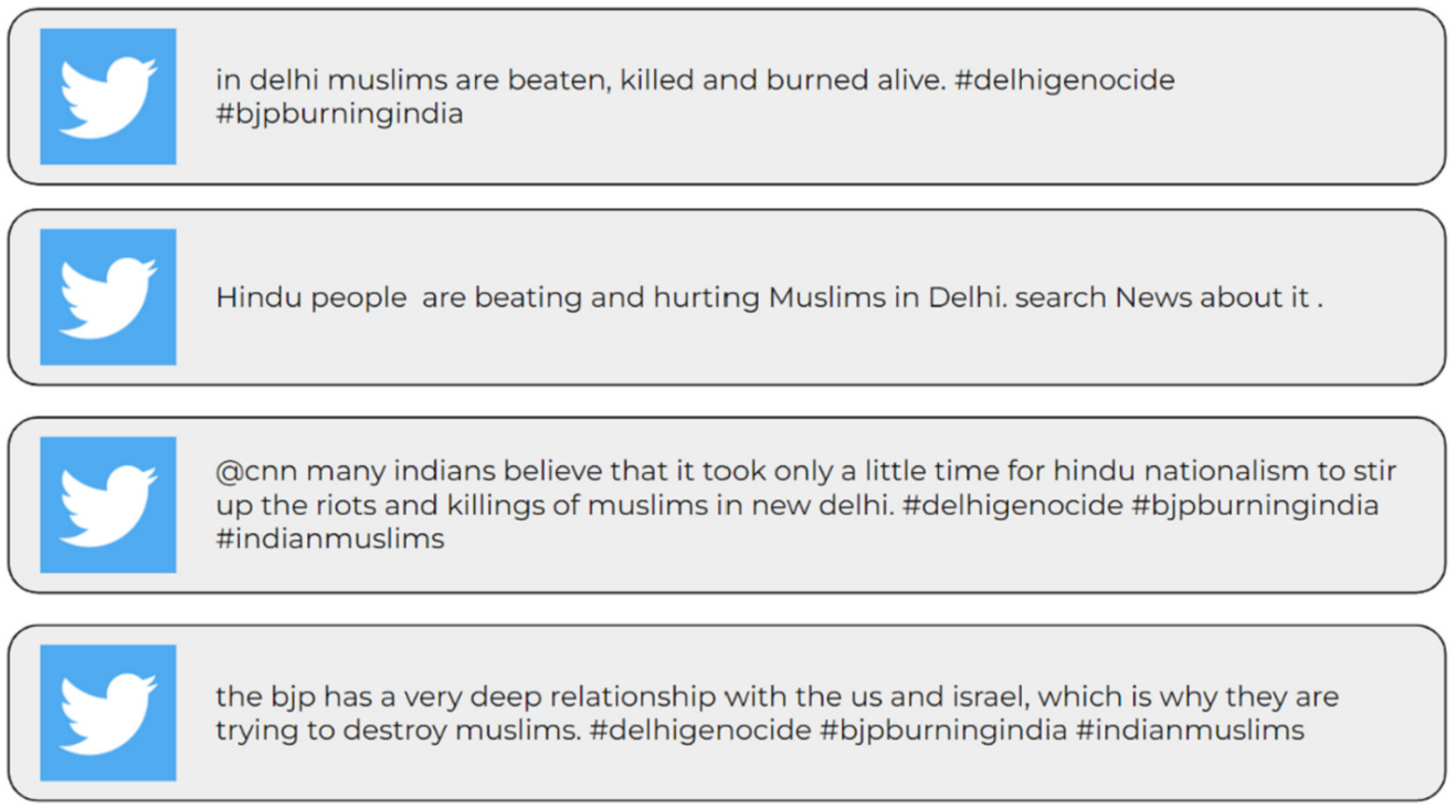

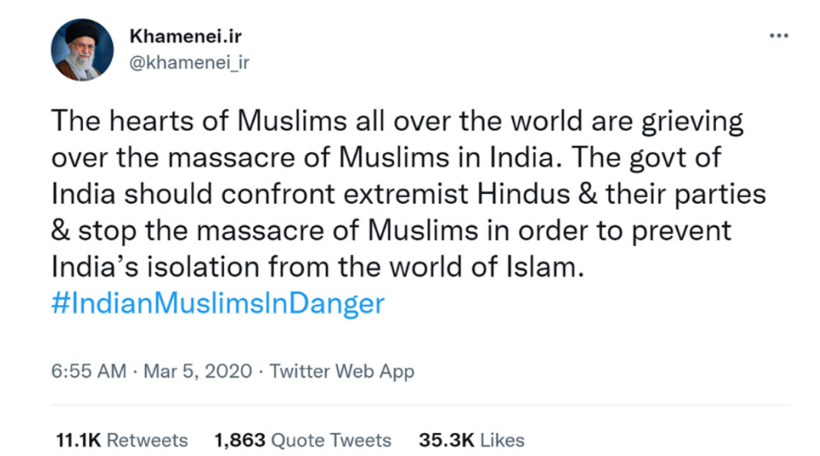

The information operation launched by Iranian trolls in the aftermath of the Delhi riots, which took place during former U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to India’s capital in March 2020 is particularly illustrative of the ways in which anti-Hindu disinformation can be leveraged geostrategically. In this case, Iranian trolls proclaimed theories about Hindus murdering Muslims on the streets of Delhi in bloodthirsty, brutal ways. Below are sample tweets that adhere to the aforementioned messaging:

Iranian troll accounts masqueraded as human rights activists, journalists and “humanists” and tagged newspapers (@cnn, @msnbc), calling on them to condemn India for anti-Muslim violence. Iranian trolls deliberately suggested that Hindus were committing genocide against Muslims while unilaterally portraying Hindus with genocidal bloodlust. Iranian trolls thus use covert influence and hijack social justice rhetoric to promote anti-Hindu disinformation.

The same messaging is seen directly from the Supreme Leader of Iran:

It appears that Iranian state sponsored trolls use influence operations and social justice propaganda to create communal divides in India. Given that India has strengthened relations with Israel over the last several years, Iranian trolls have drawn parallels between Kashmir and Palestine (Khamenei.ir, 2018). As the connection between political events and the volume of Hinduphobic Iranian troll activity demonstrates, Anti-Hindu disinformation fluctuates with geopolitical incentives. Iran’s role as mediator between India and Pakistan becomes more substantial as conflict between the nations grows.

Conclusions

We conducted the largest quantitative analysis to our knowledge on the growth of modern day manifestations of online Hinduphobia. Our analysis combines the use of topic expertise and machine learning to deduce underlying anti-Hindu tropes. The analysis shows a systemic structure of consistent themes ranging from exoticizations, barbarism and heresy, as well genocidal and tyrannical evil. We found that demeaning Hinduphobic themes were often depicted alongside elevated depictions of in-group supremacy among the memes of the extremist groups disseminating them. Proliferating exponentially in the digital age, Hinduphobia appears to be reaching new audiences and fueling the group supremacy and feelings of ethnic superiority across the ideological and extremist religious spectrums. These large surges in ethnic antagonism online often presage violence against the targeted groups. Given recent inflammation of ethnic tensions (Alam, 2022), web platforms, and actors in both government and civil society need to be especially alert for surging coded slurs and imagery associated with Hinduphobia.

Recommendations

As paradigmatic and methods research in examining Hinduphobia quantitatively, this study aims to generate widespread awareness of disinformation regarding Hindus. Recognition of the real-world impacts of Hinduphobia and disinformation — shown through correlating violence against Hindus — may prove an example to students and learners worldwide of the importance of media literacy and digital citizenship. Several key recommendations follow from our research:

● Platforms need to be made aware of this rise in Hinduphobic hate. We need digital ethnographic understanding of Hinduphobia and other hates to better support detection. Platforms need to take better measures to understand these threats.

● Given the historically murderous nature of Hinduphobia, the Hindu community should update security measures and better protect itself. It should also seek to partner with other vulnerable communities through interfaith organizations to address common security concerns and mediation. Growing community relationships and education for law enforcement, civil society and interfaith dialog can help raise awareness about the growing problem.

● Understanding the entire dimensions of Hinduphobia from the entire ideological spectrum and from its history to present day is critical to understanding the current landscape of Hinduphobia in the cyber social domain.

References

Viswanathan, I. (n.d.). Working Definition of Hinduphobia. Understanding Hinduphobia. https://understandinghinduphobia.org

Rummel, R J. Death by Government. New Brunswick, N.J: Transactions Publishers, 1994. Print.

Balaji Murali, and Sachi Edwards. “#Hinduphobia Hate Speech, Bigotry, and Oppression of Hindus through the Internet.” Digital Hinduism Dharma and Discourse in the Age of New Media, Lexington Book, Lanham, 2017, pp. 111–125.

Relia, K., Li, Z., Cook, S. H., & Chunara, R. (2019, January 31). Race, Ethnicity and National Origin-based Discrimination in Social Media and Hate Crimes Across 100 U.S. Cities. arXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.00119

France-Presse, A. (2022, June 19). ISIS Claims Kabul Gurdwara Attack, Cites Prophet’s “Insult”: Report. NDTV.com. https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/islamic-state-claims-kabul-gurdwara-attack-cites-insult-to-prophet-3080345

Middle East Media Research Institute. (2022, June 10). Palestinian Islamic Scholar Nidhal Siam At Al-Aqsa Mosque Rally: The Only Response To The “Cow-Worshipping” Hindus’ Affront To The Prophet Muhammad Is To Declare Jihad To Eradicate Them. MEMRI. https://www.memri.org/tv/aqsa-mosque-anti-india-rally-muhammad-controversy-jihad-infidels-in-line-eradicate-the-filthy-hindus

X. (n.d.). Twitter Moderation Research Consortium. X Transparency. https://transparency.twitter.com/

smat. SMAT. (n.d.). https://www.smat-app.com/

Zannettou, S. Finkelstein, J., Bradlyn, B. and Blackburn, J., 2018. A quantitative approach to understanding online antisemitism. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.01644.

Vylomova, E., Rimell, L., Cohn, T., & Baldwin, T. (2016, August). Take and Took, Gaggle and Goose, Book and Read: Evaluating the Utility of Vector Differences for Lexical Relation Learning. ACL Anthology. https://aclanthology.org/P16-1158/

arXiv, E. T. from the. (2015, September 17). King – Man + Woman = Queen: The Marvelous Mathematics of Computational Linguistics. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/

Zannettou, Savvas, et al. “On the origins of memes by means of fringe web communities.” Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference 2018. 2018.

Pajeet. Wiktionary, the free dictionary. (n.d.). https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pajeet

Pajeet. Urban Dictionary. (n.d.). https://www.urbandictionary.com/

Bard Center for the Study of Hate. (2019). Earnest Manifesto. https://bcsh.bard.edu/files/2019/06/

Hayden, M. E. (2020, January 30). White Nationalist State Department Official Still Active in Hate Movement. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/

Glitsos, L., & Hall, J. (2019). The pepe the frog meme: An examination of social, political, and cultural implications through the tradition of the Darwinian absurd. Journal for Cultural Research, 23(4), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/

Bhandarwar, A. H., Bakhshi, G., Tayade, M. B., Chavan, G. S., Shenoy, S., & Nair, A. S. (2012). Mortality pattern of the 26/11 Mumbai Terror Attacks. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 72(5), 1329–1334. https://doi.org/10.1097/

Goforth, C. (2021, December 9). “he’s letting the censors run wild”: The far-right believes Twitter’s new CEO is leading a purge against them. The Daily Dot. https://www.dailydot.com/debug/

Mong. Urban Dictionary. (n.d.-a).https://www.urbandictionary.com/

Pajeet|Tiktok Search. TikTok. (n.d.). https://www.tiktok.com/discover/

Singam, Kalicharan Veera. “The Islamic State’s Reinvigorated and Evolved Propaganda Campaign in India.” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 12.5 (2020): 16-20.

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). State Department Terrorist Designation of Hizbul Mujahideen. U.S. Department of State. https://2017-2021.state.gov/state-department-terrorist-designation-of-hizbul-mujahideen/

India-Iran Joint Statement during Visit of the President of Iran to India (February 17, 2018). Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2018, February 17). https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/29495/

Khamenei.ir. (2018, February 5). Helping Palestinians and solidarity with Kashmir are among Muslims’ key duties. Khamenei.ir. https://english.khamenei.ir/news/

Alam, J. (2022, June 10). Anger Erupts in Bangladesh, India Over Comments About Islam. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2022/06/

___________________________

Disclaimer: Views expressed here are personal.